Atherosclerosis of Aorta

What is atherosclerosis of the aorta? Atherosclerosis of the aorta is a progressive buildup of plaque in the largest artery in your body, called your aorta. This condition is also known as aortic atherosclerosis. Plaque is a sticky substance made of fat, cholesterol and other components. Plaque starts forming in your arteries during childhood, and it gradually builds up more as you get older. Plaque can form anywhere in your aorta, which is more than 1 foot long and extends from your heart to your pelvis. However, severe plaque buildup is most likely to occur in your abdominal aorta. This is the section of your aorta that runs through your belly. People who have aortic atherosclerosis may also have plaque in other arteries throughout their body. These include the arteries that supply blood to your heart (coronary arteries) and brain (carotid arteries). That’s because atherosclerosis is a systemic disease, meaning it affects your entire body. So, plaque buildup in one artery often signals you have plaque in other arteries, too.

How does atherosclerosis of the aorta affect my body? Atherosclerosis of the aorta leads to plaque buildup in your aorta. This is the major pipeline that sends out blood to your entire body. Many smaller arteries branch off your aorta to carry oxygen-rich blood in different directions (like up to your brain and down to your legs). Atherosclerosis in your aorta disrupts the normal flow of blood through your aorta and to the rest of your body. So, it raises your risk of ischemia (lack of oxygen-rich blood) in many different organs and tissues. When you think of plaque buildup in your artery, you probably imagine a piece of plaque getting bigger until it blocks blood flow. While this can happen in some of your arteries, it’s less likely to happen in your aorta. That’s because your aorta has a wide diameter. So, blood can still flow through even if there’s plaque along your aorta’s walls. The main problem with plaque buildup in your aorta is that it raises the risk of an embolus. An embolus is any object that travels through your bloodstream until it gets stuck and can’t go any further. When an embolus is stuck in one of your arteries, it immediately blocks your blood flow. Plaque growth is gradual, like soap scum building up in the pipe below your bathroom sink. But an embolus is a sudden blockage. It’s as if you dropped the cap to your toothpaste straight down into the drain. The cap would become lodged in the pipe and block water flow.

Thromboembolism, which is made of blood. Blood clots can form on the plaque’s surface. One of these blood clots can then break away from the plaque and travel through your bloodstream. Atheroembolism, which is made of cholesterol crystals from the plaque. The plaque itself can rupture (break open). A piece of the plaque can then break away and travel through your bloodstream. Atheroembolisms are less common than thromboembolisms. In either case, an object is traveling through your blood when it shouldn’t be. These emboli are the main complication of aortic atherosclerosis. How an embolus affects your body depends on where it ends up getting stuck. The embolus blocks blood flow to that area, leading to ischemia (lack of oxygen-rich blood). Without enough oxygen, the organ and tissues in that area quickly become damaged.

How serious is atherosclerosis of

the aorta?

Atherosclerosis of the aorta can

lead to a life-threatening medical emergency. This happens when an embolus

breaks away from the plaque and travels somewhere else in your body, blocking

blood flow there.

Atherosclerosis of the aorta raises

your risk of medical emergencies, including:

Acute ischemic colitis: Blocked

blood flow to your colon.

Acute limb ischemia: Blocked blood

flow to your limbs, usually your legs.

Myocardial infarction (heart

attack): Blocked blood flow to your heart.

Renal infarction: Blocked blood flow

to your kidneys.

Splenic infarction: Blocked blood

flow to your spleen.

Stroke or transient ischemic attack

(TIA): Blocked blood flow to your brain.

Plaque buildup in your aorta can

also weaken its walls and raise your risk for an aortic aneurysm. Aneurysm

ruptures and dissections can be fatal and require immediate medical attention.

Who does atherosclerosis of the

aorta affect?

Atherosclerosis of the aorta can

affect anyone. It’s a common condition. Your risk goes up as you get older.

What are the symptoms of atherosclerosis

of the aorta?

Plaque can build up in your aorta

for many years without you noticing any symptoms. In fact, you may not have any

symptoms until an embolism travels through your blood to another part of your

body. In that case, your symptoms depend on where the embolism is lodged and

what part of your body is deprived of oxygen.

An embolism can lead to several

different medical emergencies, each with specific symptoms.

Symptoms of a heart attack

- Anxiety or a feeling of “impending

doom.”

- Chest pain.

- Dizziness or fainting.

- Heart palpitations.

- Nausea or vomiting.

- Pain or discomfort in your shoulder,

arm, neck or jaw.

- Sweating.

Women and people designated female

at birth (DFAB) may also experience:

- Fatigue.

- Shortness of breath.

Symptoms of a stroke

- Dizziness or loss of balance.

- Slurred or confused speech.

- Sudden numbness or weakness in your

face, arms or legs. This may occur on one side of your body.

- Sudden, severe headache.

- Sudden trouble speaking or

understanding others.

- Trouble seeing in one or both eyes.

- Trouble walking.

Symptoms of acute limb ischemia

- Cool skin.

- Gangrene.

- Mottled skin. This means you can see

a blotchy pattern of red, purple or brown lines.

- Numbness or tingling.

- Pale or blue skin.

- Weak pulse or no pulse in the

affected limb.

Symptoms of blocked blood flow to

organs in your belly

- Blood in your poop.

- Diarrhea.

- Nausea.

- Pain or tenderness in your belly.

Symptoms of an abdominal aortic

aneurysm (AAA)

Atherosclerosis of the aorta is also

associated with abdominal aortic aneurysms (AAAs). That means the plaque

buildup may not directly cause the AAA, but the two conditions share similar

risk factors and often occur together. Many people don’t have symptoms of an

AAA until it’s close to rupturing. If you do have early symptoms, they may

include:

- Back, leg, or belly pain that

doesn’t go away.

- Pulsing sensation in your belly,

like a heartbeat.

Signs of a ruptured AAA include:

- Clammy, sweaty skin.

- Dizziness or fainting.

- Fast heart rate.

- Nausea and vomiting.

- Shortness of breath.

- Sudden, severe pain in your belly,

lower back or legs.

What causes atherosclerosis of the

aorta?

Damage to your aorta’s inner lining

(endothelium) causes atherosclerosis to begin. This damage occurs gradually,

over many years.

Certain conditions damage your

endothelium and raise your risk of developing atherosclerosis. These include:

- Smoking or using tobacco products.

- Hyperlipidemia (high cholesterol).

- Hypertension (high blood pressure).

- Hyperglycemia (high blood sugar).

- Autoimmune diseases and

inflammation, especially large vessel vasculitis.

How is atherosclerosis of the aorta

diagnosed?

Healthcare providers use imaging

tests to diagnose aortic atherosclerosis and see how far it’s progressed. These

tests include:

- Computed tomography (CT) scan.

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

- Transesophageal echocardiogram.

What is the treatment for

atherosclerosis of the aorta?

Aortic atherosclerosis treatment

focuses on:

- Lowering your risk of complications.

- Slowing down disease progression.

Medications and lifestyle changes

can help with both of these goals. Your provider may recommend medications

including:

- Anticoagulants or antiplatelet

medications to lower your risk of blood clots.

- Antihypertensive medication to

manage your blood pressure.

- Statins to manage your cholesterol.

Lifestyle changes are also

important. Your provider may recommend you:

- Avoid foods high in saturated fat

and cholesterol.

- Avoid foods and drinks high in

sugar.

- Exercise more often.

- Lower your salt intake.

- Quit smoking or using tobacco

products.

If aortic atherosclerosis has led to

complications, your provider will treat those conditions. Treatments vary

widely based on where and how damage occurred and may include:

- Amputation.

- Dialysis.

- Medications.

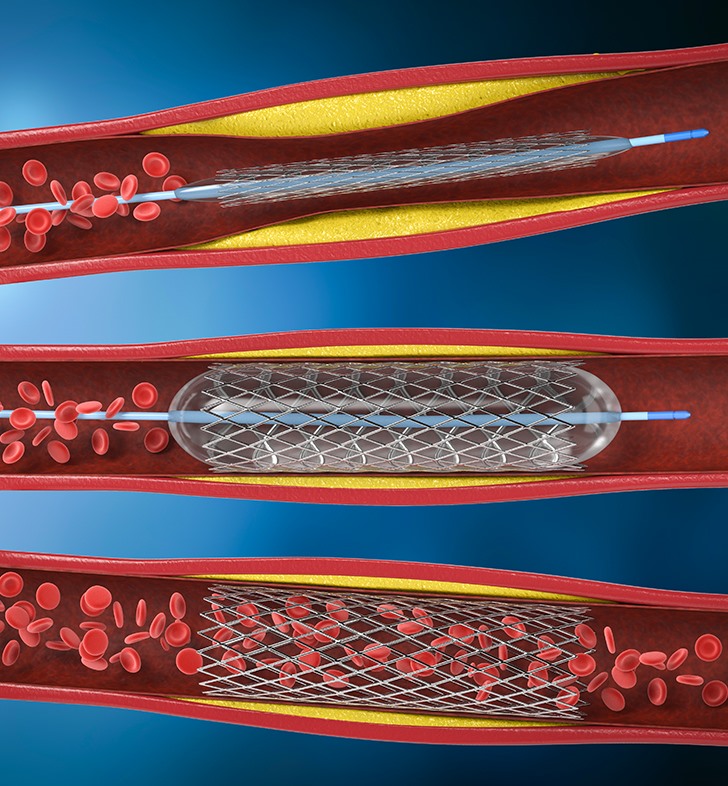

- Minimally invasive procedures.

- Surgery.

Talk with your provider about the

best treatment options for you and why they’re needed.